By Abdirezak Hassan

The documentary record shows two separate decolonizations in 1960 and a voluntary union. Israel’s 2025 recognition makes the case harder to dismiss with slogans.

Editor’s Note

This does not begin by demanding a conclusion; it begins by examining what the primary record shows. Using contemporaneous UK and UN documents and Somaliland’s 1960 Gazette, it reconstructs what happened around independence and union in 1960, then notes how today’s recognition debate is being reshaped—most visibly by Israel’s December 2025 announcement. Somalia rejects Somaliland’s claim; the aim here is to inform readers unfamiliar with the documentary history and to explain why the issue remains contested.

A debate trapped in slogans

When Somaliland is mentioned in global forums, the discussion often begins and ends with a single sentence: “Somaliland is part of Somalia.” That sentence is widely repeated because Somalia is internationally recognized and because African diplomacy has long feared that any recognition of Somaliland could encourage new border disputes. But a slogan is not an argument. The Somaliland question turns on something more specific: what exactly happened in 1960, what kind of union was formed, and what has existed in practice since the collapse of Somalia’s central state.

Somaliland’s claim is not that borders should be redrawn at will. It is that Somaliland was already a sovereign entity in 1960, entered a voluntary union with the newly independent State of Somalia, and later restored its independence after that union failed politically and institutionally. Whether one agrees or not, this is a historically distinctive case—and the primary documents are unusually clear.

Two independences, not one

The crucial fact many commentators skip is that Somaliland and Somalia did not emerge from decolonization through the same legal track. British Somaliland (the Somaliland Protectorate) was administered by the United Kingdom. Italian Somaliland was administered first as a colony and later as a United Nations Trust Territory under Italian administration. These differences were not academic: they produced two separate independence dates and two separate international records.

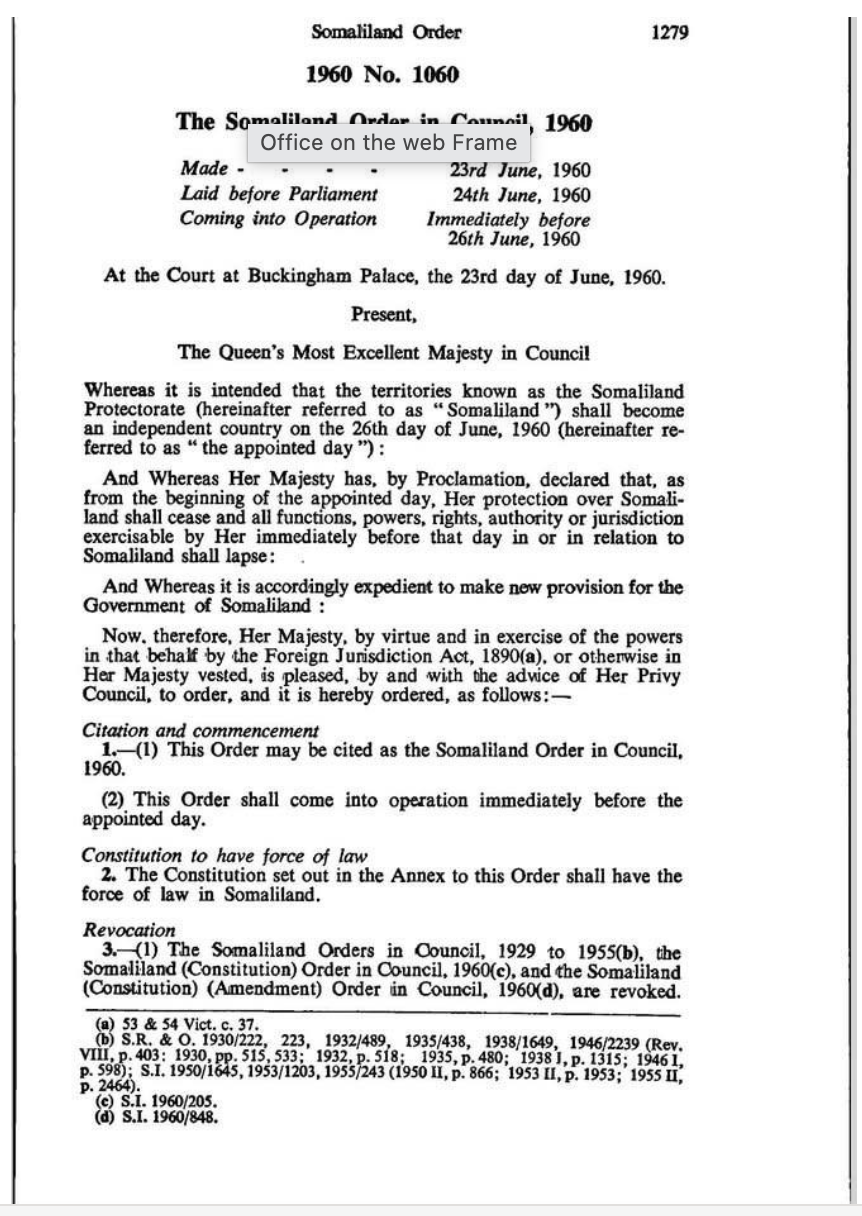

The UK’s Somaliland Order in Council (1960) states that the Somaliland Protectorate would become an independent country on 26 June 1960 and that British protection and jurisdiction would lapse. That is a sovereign termination of colonial authority.

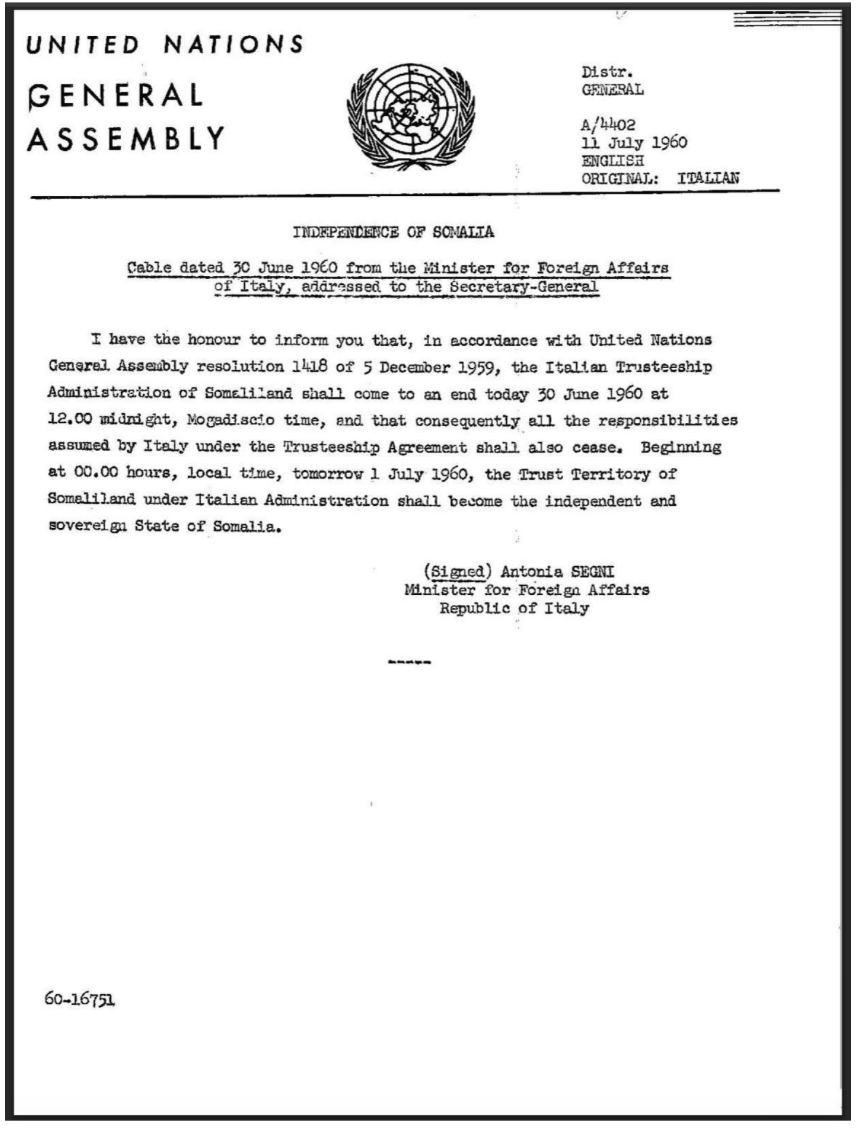

For Italian Somaliland, a UN General Assembly document (A/4402) transmits Italy’s notification that the trusteeship administration ended on 30 June 1960 and that, beginning 1 July 1960, the Trust Territory of Somaliland under Italian administration would become the independent and sovereign State of Somalia.

These are not partisan sources. They are the kinds of primary records historians and international lawyers rely on: a British legal instrument and an official UN document.

The union was voluntary—and recorded as such

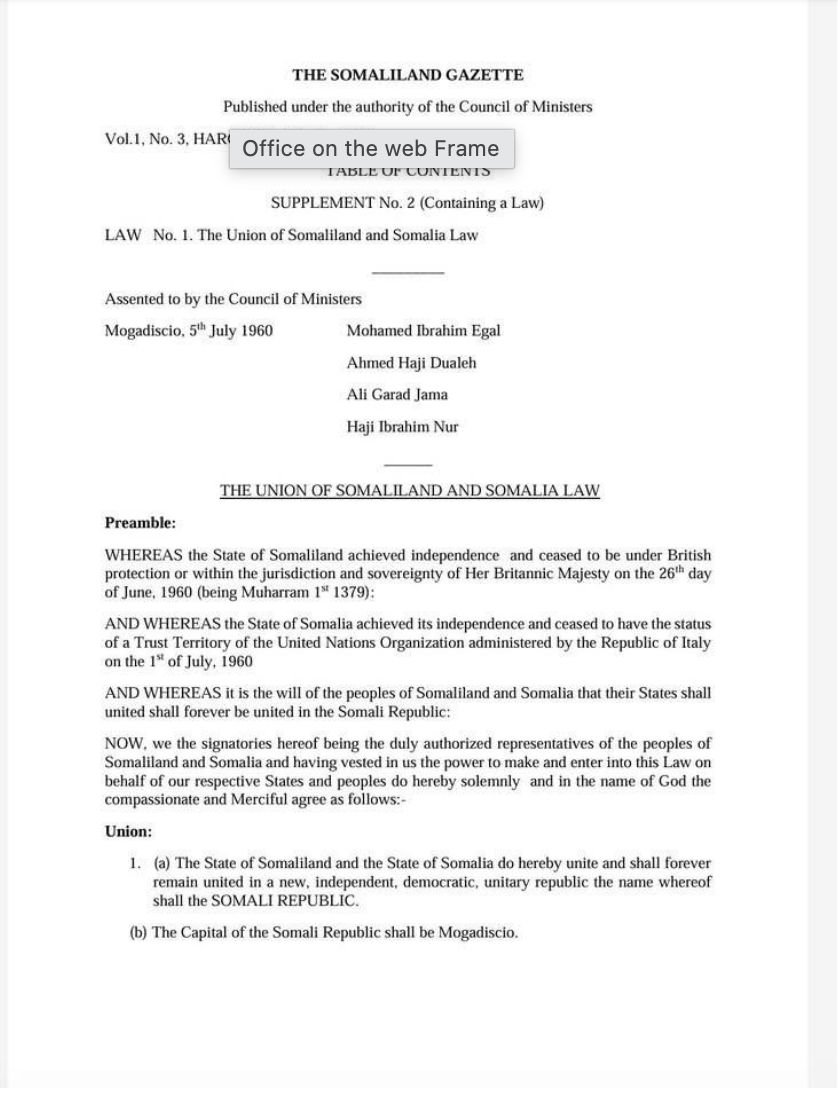

If Somaliland was independent on 26 June and Somalia on 1 July, how did one state appear on maps? Through a union. And crucially, Somaliland’s own official record—published in The Somaliland Gazette on 5 July 1960—frames the act as a union of two states. The preamble refers to “the State of Somaliland” achieving independence on 26 June 1960 and “the State of Somalia” achieving independence on 1 July 1960, and then records their agreement to unite.

This matters because it changes what Somaliland is asking the world to consider. Somaliland is not asking for a new, invented sovereignty. It is arguing for the restoration of an earlier sovereignty that was voluntarily pooled and later reclaimed when the union ceased to command consent and ceased to function effectively.

Why Somalia’s claim is challenged

Somalia’s government rejects Somaliland’s position and invokes territorial integrity—an argument strengthened by Somalia’s UN membership and international recognition. Somaliland’s counterargument is that territorial integrity is not a substitute for legitimacy when consent and effective governance have fractured for decades.

In international practice, statehood debates often turn not only on legal origin but on effectiveness—who actually governs and delivers public authority. On that functional test, Somaliland’s supporters point to concrete, long-running evidence: for more than three decades (since 1991), Somaliland has operated its own executive institutions, legislature, courts, and civil administration; it has maintained separate security forces that provide day‑to‑day policing and territorial control; and it has repeatedly held competitive elections and transfers of authority without national‑level violence of the kind that typically accompanies contested successions. These are the practical reasons Somaliland argues Somalia’s claim is challenged not just on paper, but in lived governance.

Recognition: Israel’s 2025 move changes the conversation

For years, Somaliland lived in a diplomatic gray zone: engaged quietly, praised for relative stability, but denied formal recognition out of fear of precedent. That barrier shifted when Israel announced on 26 December 2025 that it officially recognized Somaliland as an independent and sovereign state and signed a joint declaration with Somaliland’s president.

Israel’s government framed the recognition as a sovereign diplomatic decision aimed at opening full relations and linked it to the “spirit” of the Abraham Accords. Analysts also point to Somaliland’s strategic geography near the Gulf of Aden–Red Sea corridor and the appeal of a comparatively stable partner in a volatile maritime neighborhood.

Somalia condemned the move and the issue reached the UN Security Council, but the Council did not speak with one voice. Some members criticized Israel’s decision as destabilizing and warned it could inflame tensions in the Horn of Africa; others emphasized that recognition is a sovereign act of states and argued Israel has the right to recognize whom it chooses; and several delegations adopted a more neutral posture, focusing on de‑escalation and regional stability. That range of reactions underscores why any recognition pathway tends to be politically sensitive. It also confirms a new reality: Somaliland is no longer merely an academic argument. It is now an active question in high‑level diplomacy.

What the documents show at a glance

Readers new to the Somaliland case can start with the documents themselves. Document E (UK Order in Council) records the end of British authority and the independence of Somaliland on 26 June 1960. Document A (UN A/4402) records the transition of the UN Trust Territory to the independent State of Somalia on 1 July 1960. Document C (Somaliland Gazette) records the union as a union between two states. Together, these establish the core historical frame Somaliland relies on.

A responsible way forward

Support for Somaliland does not require hostility toward Somalia. A responsible approach is to acknowledge Somalia’s concerns while also acknowledging the documentary record and the governance reality. Policymakers have options short of immediate full recognition—structured engagement, trade and technical links, security cooperation, and phased diplomatic representation—while encouraging dialogue that treats Somaliland as a special case anchored in decolonization documents rather than as a generic secessionist precedent.

The world can choose to delay recognition. But it should not do so by pretending Somaliland is merely a “breakaway region.” The record shows two independences, a voluntary union, and a long period of separate governance. Israel’s recognition has forced that record back onto the table. The remaining question is whether others will finally debate Somaliland on the basis of facts rather than formulas.

Document E. United Kingdom, The Somaliland Order in Council (1960), establishing Somaliland’s independence date (26 June 1960) and ending British jurisdiction.

Figure E: United Kingdom, The Somaliland Order in Council (1960), establishing Somaliland’s independence date (26 June 1960) and ending British jurisdiction.

Document A. United Nations General Assembly document A/4402 (11 July 1960), transmitting Italy’s notification that the UN Trust Territory under Italian administration became the sovereign State of Somalia on 1 July 1960.

Figure A: United Nations General Assembly document A/4402 (11 July 1960), transmitting Italy’s notification that the UN Trust Territory under Italian administration became the sovereign State of Somalia on 1 July 1960.

Document C. The Somaliland Gazette (Hargeisa, 5 July 1960), publishing the ‘Union of Somaliland and Somalia Law’ and describing union between the State of Somaliland and the State of Somalia.

Figure C: The Somaliland Gazette (Hargeisa, 5 July 1960), publishing the ‘Union of Somaliland and Somalia Law’ and describing union between the State of Somaliland and the State of Somalia.

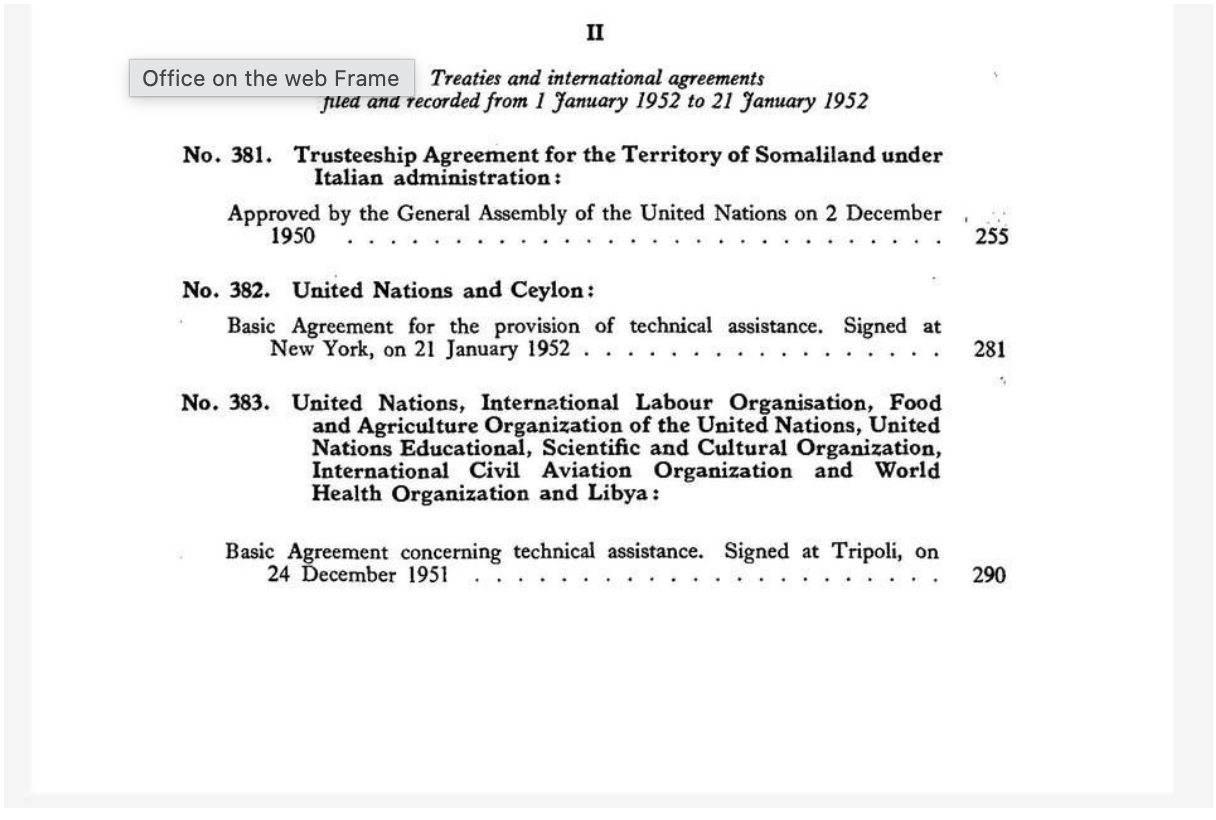

Document B. UN treaty record index noting the Trusteeship Agreement for the Territory of Somaliland under Italian administration (approved by UNGA, 2 December 1950).

Figure B: UN treaty record index noting the Trusteeship Agreement for the Territory of Somaliland under Italian administration (approved by UNGA, 2 December 1950).

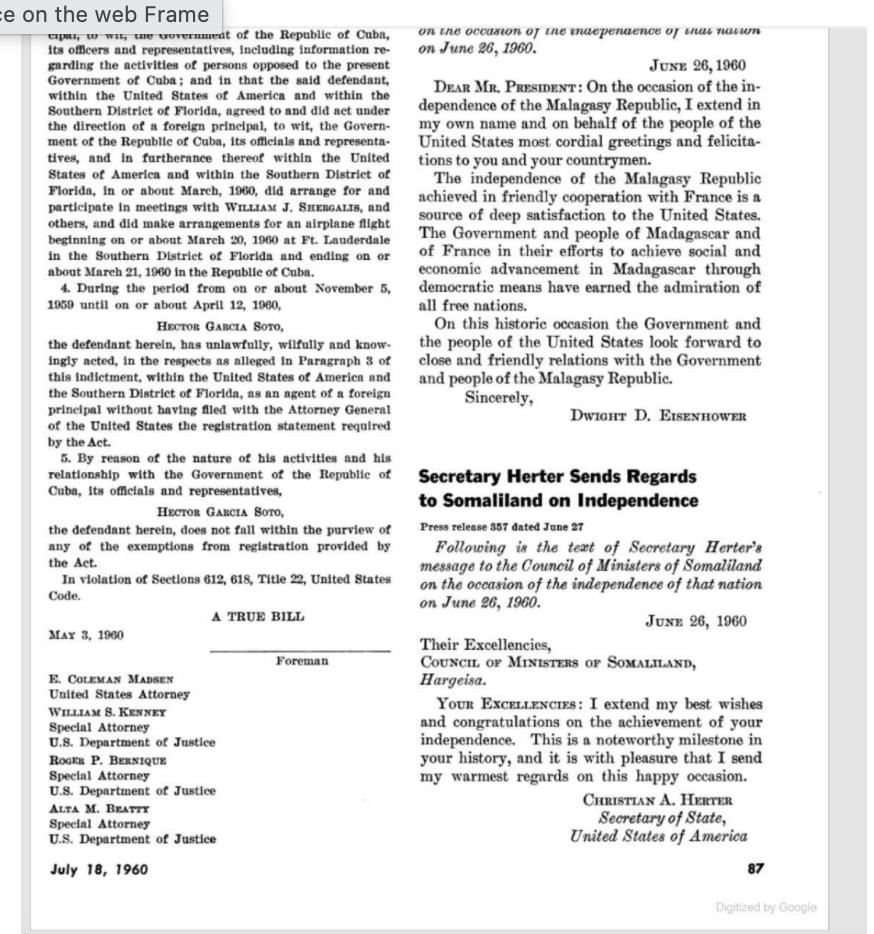

Document D. U.S. State Department press material (1960) showing Secretary of State Christian A. Herter’s message congratulating Somaliland on independence (26 June 1960).

Figure D: U.S. State Department press material (1960) showing Secretary of State Christian A. Herter’s message congratulating Somaliland on independence (26 June 1960).

Document F. Excerpt from The Jewish Encyclopedia’s entry ‘Havilah’ referencing Zeila; included as a cultural-historical note (not dispositive for modern legal status).

Figure F: Excerpt from The Jewish Encyclopedia’s entry ‘Havilah’ referencing Zeila; included as a cultural-historical note (not dispositive for modern legal status).

Author bio

Abdirezak Hassan writes on Somaliland’s history, governance, and international recognition debates.

References

-

Prime Minister’s Office (Israel), “Israel recognizes the Republic of Somaliland as an independent and sovereign state” (26 Dec 2025). https://www.gov.il/en/pages/israel-recognizes-the-republic-of-somaliland-as-an-independent-and-sovereign-state-26-dec-2025

-

United Kingdom, “Somaliland Order in Council 1960 (S.I. 1960/1060)” (as enacted PDF). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1960/1060/pdfs/uksi_19601060_en.pdf

-

United Nations Digital Library, “Independence of Somalia: cable dated 30 June 1960 …” (A/4402, 11 Jul 1960). https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/827891

-

Union of Somaliland and Somalia Law (Somaliland Gazette, 5 Jul 1960), scanned PDF. https://citizenshiprightsafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Somalia-and-Somaliland-Union-Law-1960.pdf

-

United States Department of State (archived), “Background Notes: Somalia” (historical context on trusteeship and independence timing). https://1997-2001.state.gov/background_notes/somalia_0798_bgn.html

-

UN Meetings Coverage, “Israel’s Recognition of Somaliland Triggers Sharp Divides…” (SC/16270, 29 Dec 2025). https://press.un.org/en/2025/sc16270.doc.htm

-

The Times of Israel, reporting on Israel’s recognition of Somaliland and discussing the strategic and diplomatic context (Dec 2025). https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-becomes-first-country-to-recognize-breakaway-somaliland-as-independent-state/